Fine art, theater and musical performance are all under the bountiful umbrella of “the arts.” When it comes to building facilities to support these specialty areas though, distinctions—requiring expert knowledge—begin. From meeting standards for atmospherically sensitive exhibit galleries, to flexible stage lighting and finely tuned room acoustics, construction know-how needs to be equally finely tuned.

A look at recent work by Consigli’s cultural facilities teams explores the unique knowledge needed to build three distinctively different arts facilities.

To transform a Renaissance Revival mansion—built in 1927 for the Boston Archdiocese—into a technically sophisticated teaching museum for Boston College, the team used their masonry expertise to integrate sensitive museum systems and a modern building addition.

To turn New York’s oldest surviving theater, built in 1855, into an out-of-the-box contemporary venue for the performing arts, the team’s historic restoration knowledge guided the installation of 21st-century theater systems into a 19th-century building.

And, to assure the new Recital Hall at Phillips Exeter Academy met both its design and acoustical intent, the team built a building information model to coordinate the multi-layered acoustical system, in symphony with the hall’s furnishings and finishes.

To the art of building for the arts, Consigli’s teams bring masterful knowledge.

Boston College’s McMullen Museum of Art: From Masonry Mansion to Teaching Museum

When Boston College acquired the Renaissance Revival palazzo at 2101 Commonwealth Avenue, it was soon clear this early 20th-century mansion would make the perfect new home for the McMullen Museum of Art, the college’s teaching museum. With a permanent collection and regular exhibitions, the Museum’s mission would benefit from the doubling of gallery space the palazzo promised, and a new, much more prominent location on the Brighton campus.

First though, much construction ingenuity was needed to transform this masonry building—built in 1927 for the Boston Archdiocese—into a contemporary fine arts facility. Highlights are impressive—from raising the mansion’s roof two feet without altering its profile, to integrating sensitive interior environmental systems, to assuring the porous brick-and-limestone building would be a watertight haven for art.

The renovation, designed by Boston-based architects DiMella Shaffer, preserved the façade of the original 23,000-square-foot building, while expanding it with a two-story, 7,000-square-foot glass-wrapped atrium addition, at the building’s eastern end. Today, the atrium is a welcoming entrance beacon, providing access to the palazzo’s first-floor conference facilities and the two upper gallery floors. Visitors have views of Boston and the larger Brighton campus from its glass-clad spaces and rooftop terrace.

The McMullen’s Director, Nancy Netzer, in her online “Director’s Welcome,” describes what makes the McMullen so special—and why more space was vital. “From its inception the McMullen has linked its mission to faculty research across disciplines and methodological frontiers and to sharing new faculty scholarship with a wide audience.”

“With this building the McMullen joins the ranks of this country’s finest university museum facilities,” said Netzer, at the museum’s opening this fall.

To build the much-needed museum, Consigli’s team brought the in-house masonry expertise required to raise the roof, seal the exterior masonry walls so they would become the air-barrier needed to maintain the museum’s sensitive interior environment, and build the glass atrium into an existing exterior wall. When finished, that limestone exterior wall had become an interior wall, and a visual transition between the contemporary design of the addition and the palazzo.

Consigli’s Project Manager, Adam Gordon, fresh from renovations for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, brought Boston College (BC) his expertise in fine arts facilities.

Gordon explained some of the challenges, “To renovate a masonry building like this, with its monolithic exterior masonry walls and low deck-to-deck heights, into the environment fine art needs, we need to understand the existing building really well. We knew BC wanted to maximize the ceiling heights in the galleries.

“As soon as we finished the gut demolition of the second and third floors, we did a laser scan of the building. This scan was the foundation for our building information model. It helped us really nail down the routing and how to fit a modern day infrastructure into the building’s historic framework.”

One important discovery from the scanning was the clarification of the roof’s rib spacing. From the scans it was clear that the drawings were off by a foot for each rib. Where the team thought there was an open bay in the roof’s structure—available for the installation of the new mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems—the way was blocked by a very solid roof rib.

“Building scans are like GPS—they help us figure out the best routes for the miles of conduits and piping we need to install for new environmental and utility systems,” Gordon said.

And, to assure that the team was using the best material to create an air-barrier on the inside of the masonry exterior walls, experimentation was needed. “Once we had all the interior walls demolished and it revealed the masonry on the inside, we went through a series of mockups with the architect and with our water-proofer to come up with a product that would work in these conditions,” detailed Gordon

An intriguing part of the project was raising the original roof by a full two feet, the additional space needed for the galleries below and the infrastructure systems that would maintain their temperature and humidity levels.

Consigli’s Project Engineer, Pat Gildea, explained this process, his favorite part of the project. “Before we could raise the roof, we needed to dismantle and remove the roof’s stone parapet. Imagine needing to take down a fence of stone pillars—and then put it back together. That’s what this was—except we were three stories up. To do this we first cut the parapet into slices, and then had a crane—which we set on the roof—move the stone sections to the ground. Next, we labeled and stored them, until it was time to reinstall. Once we finished building a steel structure into the walls to support the raised roof, we rebuilt the parapet. It looks exactly the same.”

Now, the two main exhibition galleries built within the mansion’s second and third floors significantly enlarge the Museum’s previous temporary exhibition space. The Daley Family Gallery—a 4,800-square-foot space—is on the second floor, while an open-plan sculpture gallery on the third floor leads to the 925-square-foot Monan Gallery. All internal walls on both the second and third floors were removed by Consigli and replaced by eight-foot and ten-foot high movable gallery walls, at widths ranging from two, three and four feet, allowing the spaces to be tailored to each exhibition. The building’s first floor was renovated into modern conference facilities, while restoring its original interior finishes, from wood work panels and marble floors, to its early 20th-century light fixtures, which were repaired and reinstalled.

Some of the team’s work was literally artful. Consigli’s team oversaw the first installation of dramatic artwork from the McMullen’s permanent collection, a three-paneled stained glass work by 19th-century glass artist, John La Farge. Standing eight feet tall and two-and-a-half-feet wide, the triptych, originally created for Roxbury’s All Saints Unitarian Church, has a preaching Christ in the center panel, while panels of St. John the Evangelist and St. Paul grace either side.

Consigli met with artisans from Serpentino Stained Glass Studio after the studio completed the restoration of the La Farge masterpiece, to coordinate the glass panels’ new back-lit exhibit light box, being built by Consigli’s carpenters. Next, the team worked with the fine-art handling firm Artex, on the work’s installation. A four-hour process placed the artwork in the atrium lobby, where the three 150-pound panels now stand sentinel, greeting visitors with their luminescent presence, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

In addition to the newly opened McMullen, our current roster of arts projects includes other exciting expansions, among them our work for Wellesley College. In support of the college’s music and fine arts programs, we are busy with the renovation of the Jewett Arts Center, a notable mid-century modern building designed by architect Paul Rudolf. The home to Wellesley’s fine art and music departments, this comprehensive renovation is also adding 8,000-square-feet to the studio arts facilities and 4,000-square-feet of new instrumental rehearsal space. The renovation is designed to handle current and future technology, from digital imaging to film, to sculpture to music, supporting students and faculty in whole new ways to see arts and communication, sound and light. Who knows what will be possible?

Hudson Opera House: Black Box, Out-of-the-Box

The historic restoration of the Hudson Opera House, a tricky gut renovation of a 161-year-old masonry theater, is creating a performance venue with all the contemporary flexibility of a black-box theater—but in a gracious 19th-century space, instead.

Originally built in 1855, and now part of Hudson’s Historic District, the Opera House has a dramatic presence on bustling Warren Street. The final and most significant phase of multi-phased renovations, the project includes the adaptation of the performance hall for modern use, creating an intimate theater, with flexible seating for 300. When the renovation—designed by Preservation Architecture—is complete, both the Opera House’s proscenium stage, and the larger, flat-floored hall itself, will be available as performance and seating space, providing opportunities for many creative productions. These will be able to range from traditional stage productions, to theater-in-the-round in the 40-foot-tall hall, , 70-foot by 100-foot hall, and everything imaginable in-between.

Project Executive Scott Cruikshank gave a succinct overview, “It’s a pretty spectacular building. It’s big, it’s tall, it’s historic, it needs a lot of intricate structural work, and with its street-edge setting, there’s no staging area. Three sides of the building run from sidewalk to sidewalk, and its fourth side edges a 5-foot-wide alley.”

Along the way, Project Superintendent Dave Caswell and his team have tackled just about everything: addressing complicated excavations and shoring conditions inside and outside on the shoe-horned site, coordinating with the town, installing steel-plate repairs to centuries-old timber trusses, providing a design-assist role for the lighting design, to assuring that the abutting businesses and neighbors—including one who recently invested $1.5 million into their property—don’t experience problems.

The Opera House’s Executive Director, Gary Schiro, who has been working hand-in-hand with Consigli’s team, noted the many challenges the building offered, from the fact that the building overall did not have any modern mechanical systems, or that the theater space had not been updated in decades. “There were no, absolutely no mechanical systems up there, no systems at all. No mechanicals, no sound equipment, no lighting. So to figure out how to integrate all that into the space without hardwiring it completely and just turning it into a utilitarian black box, was really important to us. We have a beautiful 19th-century performance hall and we wanted to retain as much of that as possible. And that’s what Consigli is making happen. We will have terrific flexibility. We will be able to have performances in-the-round, on the stage, we’ll able to present in a great variety of ways.”

Schiro noted with great appreciation the insight Caswell and his team have brought the project, “They are such excellent problem solvers, and they are helping us save money all the time. We are enormously grateful to have Consigli on the project. Consigli are such great partners.”

In addition to developing what is in essence a contemporary black box space—though without the black paint and with a lot more history to it— the opera house restoration includes almost every front-of-house and back-of-house space: the 40-foot-high performance hall, the proscenium stage, the mezzanine, five dressing rooms, a lighting and sound booth, the “Green Room,” accessible restrooms, exterior masonry repointing, restoration of the building’s 20-foot windows, and the 20-by-20-foot addition for the theater’s first-ever elevator.

Meanwhile, the team has uncovered remnants of the Opera House’s history, in all shapes and sizes. From the missing woodwork of the theater’s long dismantled ceiling oculus (now being restored), to playbooks, tickets and posters, like ghosts of theater past. The team was excited about one find in particular—found in the attic—the building’s original “topping-off” construction celebration branch, still attached to a truss, complete with an ancient ribbon. Caswell, while marveling at the longevity of this piece of construction history, also spoke in great appreciation of what was also in the attic, the timber trusses, “The truss set-up is amazing to me. To be able to have a full length truss, 70-feet-long, from one tree, that is pretty cool.”

Phillips Exeter Academy’s Recital Hall: Sound Results

“For a facility like this, we really have to understand the acoustical intent, as much as the aesthetic intent. And there are times when the needs of the acoustical design override what the architect might want,” explains Project Manager Travis Kirby, describing the complexity of Phillips Exeter Academy’s new Music Center addition, which opened this fall.

Acoustical design requires building in a way that can be, to say the least, atypical. With walls that can’t be perpendicular because of acoustical needs, to complex ceiling, wall and floor systems that require extraordinary coordination and construction sequencing, the team has stayed on its toes—and come up with a host of creative responses to the project’s demands. Our first project with the New Hampshire-based independent school, the hall was designed by Boston architects William Rawn Associates to accommodate the growing music program. A 12,000-square-foot addition to the campus’ Forrestal-Bowld Music Center, it incorporates a recital and rehearsal hall for 250 people, a music media and technology center, four practice rooms, and a musicianship studio, where students learn to mix and produce audio recordings.

“What you don’t see, we get to see when it’s going in — that’s what’s cool. Most will never realize what makes it work acoustically, though certainly they will appreciate it, when they are in the building,” said Kirby, detailing what goes into building the acoustical design intent.

Kirby talks about what the walls, floors and ceilings hide. “People go into a recital hall and say, ‘Oh, this is awesome,’ but they don’t realize that the subfloor is up on four inches of insulation and that it is on neoprene pads to give bounce to it. They don’t realize that there’s an inch of acoustical insulation sprayed to the bottom of the deck beneath the seating, to absorb sound. Or that decorative wooden wall slats hide acoustical panels, barrel diffusers and sound dampening curtains.”

The two-phased project benefited from proactive efforts by the team. From valuable site utility investigations that saved time and money, to an in-depth re-working of the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, through an intensive building information modeling (BIM) effort to coordinate the recital hall’s ceiling construction, the team’s effort achieved sound results.

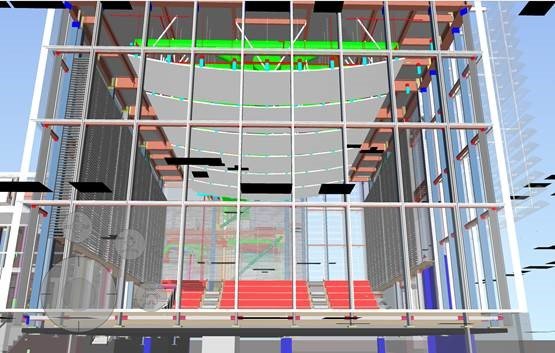

In the fall of 2015, the team moved from the site work to the hall’s construction. While the whole building is filled with sensitive systems and details, the recital hall’s ceiling—a decidedly complex affair—is of special note. Kirby describes it, “The room is 40-feet-tall and at the top, it is exposed steel and decking that is sprayed with acoustical insulation, in the center is duct work, and there is a lot of lighting. All of this is covered with an acoustical “cloud” ceiling that hangs about 30 feet above the floor. “It’s a suspended grid of six, 36-foot-long by 9-foot-wide curved gypsum panels. We needed to coordinate the structure of these “clouds”. Each needs to be braced five or six times with light-gauge metal bracing. We needed to make sure the bracing would reach the upper deck, and not hit duct work or lighting. Danielle Gray on our BIM team put the bracing shop drawings into the project’s model and we were able to clear up clashes. It was great.”

Kirby noted special team efforts that spurred the project along, from Superintendent Jerry Dorval’s conscientious coordination with the school, to Consigli’s self-perform team’s construction of a concrete foundation that needed to be at a 92.5 degree angle, to the millwork team who built and installed the hall’s dramatic 20-foot wood slat wall screen, “I’ve seen a great sense of pride. Everyone wants a good product out there.”

Exeter’s Senior Construction Project Manager, Mike Searle-Spratt, appreciated the problem-solving skills of Consigli’s Kirby and Dorval, Senior Project Manager Chris Brown and Project Engineer Mike Swett, “They gave us all the tools we needed to make decisions and keep things going. They did a nice job for us.”

Now, with the new Music Center addition complete and the school’s calendar filling with upcoming performances, Searle-Spratt says, “It is going over well. Everyone is very, very pleased.”